This site has moved to http://md-connection.zzl.org. You should be redirected there within 10 seconds. If you are not redirected automatically, please click here. Please update your bookmarks.

Articles about Moldova

This page is dedicated to publishing articles about Moldova. Probably all of them will be from foreign (western, to be precise) press, because in Moldova it's hard to find a good article, and in Russian press articles about Moldova are usually one-sided.

Jump to:

- Moldova: The Price of Sex

- A taxi ride through Chisinau in transition

- 'Hai Moldova!' National soccer team reflects countrymen

- Americans in Moldova; Moldovans in Italy...

- Pay in Europe 2007...

- Moldovans make a home in Vermont

- Moldovan Wine Industry Faces Crisis

- 15 Cents for the Bus Ride of My Life

- Transnistria - I'm back in the U.S.S.R!

- Culture buds in Moldova spring

- Moldova by TimeOut Magazine

- Asking for salsa in Moldova draws a blank look

- From sunshine to Moldova

- Moldova: A Small Wonder...

- Moldova's Curious Growth

- Wheat Swamp to Moldova a Long Way

Moldova: The Price of Sex

A documentary photo slideshow by Mimi Chakarova about sex trafficking in Moldova. The slideshow can be viewed at the PBS Frontline/World website.

A taxi ride through Chisinau in transition

August 20, 2007, by Linda Holzgreve; translation by Zoë Brogden.

Article courtesy of Linda Holzgreve, published here with her kind permission; originally published on CafeBabel.com.

The EU has begun in the west, whilst the rest of the world waits in the east: a taxi drive through the Moldovan capital

It's Sunday evening, 9 pm. The taxi arrives, and for the sake of safeness, I choose the back seat. 'Hi, I'm Ghena,' the solid, 40-year-old taxi driver says with a smile. 'Today I'm going to show you how we drive in Moldova.' Our eyes meet in the rear-view mirror, and I laugh politely. 'Moldovans take no notice of the rules of the road,' calls Ghena triumphantly. He wipes the sweat from his brow with a handkerchief; the temperature outside hovers just under 40°C. 'Let's go to the North Pole,' he jokes, as we creep into Chisinau's evening traffic.

Out of boredom, Ghena took up taxi driving 18 months ago. Apparently he's now retired. 'I used to be a policeman, he says, turning to look at me, unsure if he should go into greater detail. But his pride got the better of him. 'I used to be in OMON, a special anti-terror division.' Involuntarily, a nervous yelp leaves my throat. Ghena turns the car at a roundabout, as he wants to take me to Telecentru to show me the newly built town houses.

On the way, conversation turns to Chisinau's taxi system. Many firms exist in the city, competing on the basis of the quality and size of the vehicle. Fares vary depending on the length of the trip and the type of car: a new model is more expensive than an old one, a larger boot sets you back more than a smaller one. A ride within one of the town districts will cost in the region of 1 euro, whilst 10 euros will take you to the Nistru, the natural border to the breakaway Transnistria region.

We arrive at Telecentru. The newly-built houses disappear behind an armour of huge walls and cast iron gates. The taxi strains to keep a walking pace through the uneven cobbled streets, where a patch of roses stands side-by-side with a towering pile of sand. 'Soon this area will be tarmacked over,' explains Ghena with some eagerness.

Moldovans earn little over 100 euros per month, a level rating them the poorest nation in Europe. In contrast, property prices stand at levels comparable to the West. Who exactly demands such property to spring up from the ground? The answer is pretty instantaneous: diplomats and international organisations. Ghena seems unconcerned that the property boom has failed to reap much reward for majority of the population, he's glad that 'something is happening here at least.'

Our tour takes us to the Bulevardul Dacia which runs out of the city towards the airport and beyond into outlying villages. The longest road in Europe, according to Ghena. Huge advertising hoardings, accompanying the city traffic like a memorial, soon make way to wide country roads. Headlights from oncoming vehicles are the only light in the darkness. On the roadside, groups of young people light campfires. The atmosphere is nothing short of eerie. This Moldova seems far removed from the developments of Telecentru. When I enquire about Moldova's economic development it's met with a shrug of the shoulders from Ghena.

Nevertheless, he is optimistic: the population is young, and in the future, Moldova will make economic strides. The indications, for him, are clear enough. 'Previously we had to wait 20 years for a new car, but today fewer questions are asked. You go, buy the car, and that's it.' But cars alone can't bring happiness. Ghena hopes more Western investment will come soon, primarily in Moldovan wine exports. For him, the industry is a 'good tradition' and the land must become competitive. Turning to me, he asks whether I want to go for a drink with him. 'You can get a table in bar no problem, writing back of there isn't so easy,' he says, as we drive back towards the city centre.

Ghena responds confidently when I ask exactly why Europe should be interested in investing in Moldova. He sees his country as a republic and a potential EU member. He's convinced that 'with a bit of help we can fulfil the accession criteria. Why shouldn't we achieve what Romania has?!' Romania is always a good yardstick for Moldova, which once formed part its territory. Solidarity is now a demand of its neighbour: 'otherwise, nobody will support us.' He also regards EU candidacy as a strong parting shot to Russia, whose influence during Soviet times was greeted with much ambivalence.

Our trip is coming to end. We turn towards a bus stop as an explosion sounds a few metres in front of us. Flame and smoke ascend into the dark skies above. Without a moment to raise a protest, Ghena steers in the direction of the fire. A group of youngsters gather in front of a restaurant. Panic over! Their high spirits over a failed firework signals all is well. In the meantime, Ghena chats to one of the guests, and secures his next fare. The rules of the road really are forgotten.

'Hai Moldova!' National soccer team reflects countrymen

April 6, 2007, by Dan Fellner

Article courtesy of Dan Fellner, published here with his kind permission; originally published in The Arizona Republic.

CHISINAU, Moldova - On a cold and rainy Saturday night, I arrived at Zimbru Stadium more than an hour before the start of a EURO 2008 qualifying game between the national soccer teams of Moldova and Malta.

I wanted plenty of time to check out the capital city's newest and swankiest sporting venue, which was christened less than a year ago. As I walked around the perimeter of the 11,000-seat facility, I noticed something was missing.

There was no parking lot.

Moldova is one of Europe's poorest countries and the average salary is about $100 a month. Few people can afford their own cars. So most of the soccer fans arrived at the stadium the same way I did - by bus. A parking lot would have been wasted space.

I also noticed another difference as I priced items for sale at the concession stands. A 16-ounce cup of beer cost only 13 Moldovan lei (about $1). A bag of peanuts cost about a quarter. Prices weren't much higher than what you would pay at any supermarket in town.

Moldova, which used to be a part of the Soviet Union, has been an independent country for only 16 years. Apparently, Moldovans still have a lot to learn about something American stadiums have been excelling at for decades - price-gouging.

I headed to my seat. The stadium was starting to fill and the teams were warming up on the field. It was almost dark but they still hadn't turned on the stadium lights. The players clustered into one of the corners of the field, where there was a bit of light streaming in from the concourse. They could barely see what they were doing.

Budgets are tight in Moldova and it's not cheap to power stadium lights. Turning them on before the game actually starts is considered an unnecessary luxury.

Finally, it was game time. The lights came on and the public address announcer greeted the crowd, first in Romanian, Moldova's native language, and then in English.

"Good evening ladies and gentlemens," he said.

Okay, his English needed some work, but it was nice of him to make the effort.

Eastern Europeans tend to be reserved, even a bit stoic at times, and I expected the crowd of about 10,000 fans to sit on their hands and show little emotion. Boy, was I wrong.

The crowd was enthusiastic and loud from the opening kickoff, chanting "hai (go) Moldova," waving flags and erupting anytime Moldova threatened to score. They also tried the wave, but like the announcer's English, they could use some more practice.

A group of seven young men even spent the whole game without their shirts on, baring the 40-degree temperatures to proudly display painted chests spelling M-O-L-D-O-V-A.

Moldova wins international soccer games about as often as the Arizona Cardinals make the playoffs. When the team scored a late goal to earn a 1-1 tie, I never thought 10,000 people could make so much noise.

I found myself yelling along with everyone else. Moldova is the quintessential lovable underdog. Its economy is in bad shape and without much money, it's difficult to field competitive sports teams. The budget to build Zimbru Stadium was only $11 million, well less than Randy Johnson will earn to pitch for the Diamondbacks this season.

But the people - like the national soccer team - work hard for little compensation and seldom complain about it.

As I waited outside the stadium for my bus home, I joined the chants of those waiting alongside me: "Hai Moldova!"

Americans in Moldova; Moldovans in Italy...

March 28, 2007, by Lyndon Allin

This is a blog entry by Lyndon Allin posted at Lyndon's blog and at Global Voices Online on 28 and 29 March 2007, respectively. Republished here with kind permission from Lyndon Allin.

Alexandru Culiuc's weblog is one of the best in the Moldovan blogosphere - probably the one I enjoy reading the most, and happily it has an owner and readership that don't seem to mind my mostly English-language comments. Last year, Alex had an interesting post about foreigners' impressions of Moldova (titled "Moldova as seen by comedians and volunteers"), in which he discussed and linked to a few of the blogs written by Peace Corps volunteers (PCVs) - Americans - in Moldova.

For whatever reason, the discussion in the comment section of that post was re-started about a week ago, and I posted a couple of comments there, mainly 1) trying to stick up for an outstanding PCV blogger named Peter Myers - not that he needs me to stick up for him - who some of the Moldovans felt was being too critical of the rural school he teaches in, and 2) disagreeing with the broader notion that all PCVs are "losers" or people who haven't found themselves in American life.

My comments there are not that interesting, frankly, because they go down a well-trodden path about how criticism can be a good thing if it's constructive and digress into discussions of the American educational system and other less-than-relevant topics (though the discussion was refreshingly friendly compared to others I've been involved in recently). They are not, for example, as interesting as one of Peter's recent posts:

After class today, I noticed nearly a dozen men, of whom I know several and who are major figures in the village, standing around on the first floor of the school. I said hello and then continued upstairs. On the way to the computer lab, I saw Raisa, one of the cleaning ladies. I struck up a conversation:

"Why are practically all the men in Mereseni at the school right now?" I said, exaggerating.

"It's a Communist party meeting," Raisa said. "They want the Communists in power."

This was the first time I had heard of a local Communist party in the village, but it didn't surprise me. Before I could respond, Raisa summed up the political thinking of many Moldovan villagers, rooted in nostalgia for the times when food was cheap salaries came on time:

"I would be in favor of the Communists," she said, "if I thought that they could make things the way they were back then."

But I've already digressed from my intended point, which was to translate one of the more recent comments to the post mentioned above on Culiuc.com, written by a Moldovan living in Italy [I've translated it from Romanian, and I hope anyone who can will correct any mistakes - although I don't think there are any serious ones, my Romanian is not as good as my Russian]:

Hello to everyone from Moldova, I'm in Verona, Italy now, it's a beautiful and rich country, but you just can't imagine how much you miss those green pastures of home. Here as everyone knows there are lots of foreigners who work at very difficult jobs, there are lots of Albanians, Moroccans, Blacks, and of course Moldovans, Ukrainians and Russians.

When I get on a bus or go into a supermarket, I feel at home because if you want you can ask something in your own language. Ours is a small country and I don't understand who has stayed home if there are so many of us here. I hear a lot of compliments from the Italians about us: we learn foreign languages very easily compared to them, we are good-looking, clever, and very emotionally strong. When they have a little problem, they have to go to a psychologist, since they are very melancholic and, as they say, "Non voglio fare niente" - man, what about all the problems we have, I guess we should just die, but no, we struggle and get through it all.

My friends ask me what Moldova is like, and I don't know what to say, it's a lovely country but of course there's nothing to see there, because it's nothing compared to other places, so I tell them that all you see there is bars, good times, and drinking.

Everyone who's here wants to go home but then they come back and say that it's even worse, they shouldn't have gone because it was just a waste of money and it's sad there, but I still hope that someday we too will speak with pride about our country and lots of foreigners will come so we can show them how brave [bravii] we are.

Now I ask myself, what am I doing in a strange land with a strange language, living in a strange house, if I have a big house and an apartment at home, and all my folks are there? I don't have an answer, for some reason my plans seem to keep me here, but Moldova is still in my heart always.

Maybe it was the style of the original - stream-of-consciousness, with minimal punctuation and capitalization; I?ve added paragraph breaks and more sentence breaks in translating it - or me being too sentimental in the spring air, or who knows what else, but I found this to be one of the most moving things I have read in I don?t know how long.

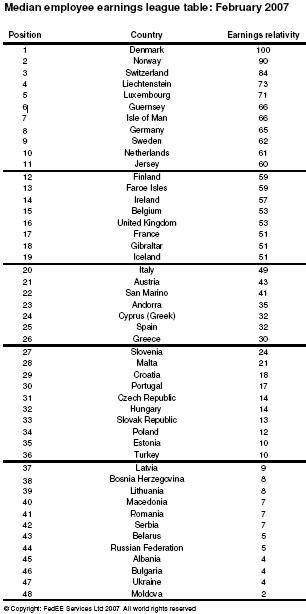

Pay in Europe 2007: Pay gap between Europe's richest and poorest countries has fallen significantly over the last six years

March 27, 2007, by Finfacts Team

Article courtesy of Finfacts Ireland, republished here with their kind permission.

The pay gap between Europe's richest and poorest countries has fallen significantly over the last six years.

According to the Federation of European Employers' (FedEE) latest Pay in Europe report, the gross median hourly earnings of employees in Denmark were 65 times (65x) higher than in Moldova on February 1st 2007. This compares with a pay gap of 70x in 2006 and 91x in 2001.

Since 2001, all countries in the bottom half of the FedEE league table, except Poland and Portugal, have been able to narrow the gap with Denmark.

Higher up in the league table, however, there have been falls in relative earnings in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Spain and the UK. Norway has now taken the number two spot from Luxembourg, with relative earnings climbing from 71% of Denmark's in 2001 to 90% in 2007.

Rewards for Climbing the Jobs Ladder

The report also reveals differences in pay between those in senior management positions and those in unskilled service sector positions within individual countries. This differential varies from 12.9x in Moldova and 11x in Latvia to just 3.9x in Norway and 4.1x in Malta and 4.4 in Ireland.

In the category of a Skilled Manual Workman, working in a large or foreign-owned firm, the following are comparative hourly rates in euro: Ireland EUR 16.04; Sweden EUR 17.34; Poland EUR 3.43 and Moldovia EUR 0.45 - 45 cent!

The Pay in Europe 2007 report provides hourly wage and salary data for 32 standard job positions in 48 European countries and territories at February 1st 2007. It is available free of charge to members of the Federation of European Employers (FedEE). Each table contains 32 standard job positions within two categories of company size or type. Hourly pay is presented in the form of a midpoint and spread to reflect the range for each job. The average is not used as it would be distorted by high earners.

Moldovans make a home in Vermont

January 14, 2007, by Lauren Ober

Article published by Burlington Free Press. Unfortunately they do not allow republishing their articles but they have kindly provided me with a permanent link to the article: please click here for full article. Below is a small excerpt from the article

Vermont's Moldovans are largely unnoticed on the spectrum of immigrants and refugees who seek haven in this state. They are a smaller, less visible group than the Somalis, the Sudanese, the Bosnians and the Vietnamese, which together number in the thousands in Vermont.

Moldovans are not refugees fleeing from a torturous regime, resettled in Vermont by government means. They tend to be educated asylum-seekers from the poorest nation in Europe who have learned to embrace the wider world as their own.

Moldovan Wine Industry Faces Crisis

June 9, 2006, by Dan Fellner

Article courtesy of Dan Fellner, published here with his kind permission; originally published in The Arizona Republic.

MILESTII MICI, Moldova - This is my kind of town.

There are 34 miles of streets, yet virtually no traffic. Crime is non-existent. The air is clean and the temperature is a constant 56 degrees year-round. It doesn't rain or snow.

And it's never hard to find a good meal and a fine bottle of wine.

In fact, Milestii Mici, an underground complex less than 10 miles from Moldova's capital city of Chisinau, houses one of the largest wine cellars in the world.

More than 1.5 million bottles and 1,300 huge oak barrels of wine dating back to the late 1960s are stored 50 yards below ground in this self-dubbed "wine town." The site, which used to be a limestone mining operation, is now one of Moldova's most popular tourist attractions.

For about $30, you get a guided tour by car along narrow streets appropriately named Cabernet, Chardonnay and Pinot. The tour includes lunch and a chance to sample six different wines. They even give you a couple of bottles to take home.

I've visited California's Napa Valley before but nothing there comes close to matching the sheer magnitude of Milestii Mici. Street after street is lined with barrels and bottles from floor to ceiling.

If your car is going to break down or run out of gas, I can't think of a better place to wait for the tow truck.

It's not just about quantity, either. The winery is also proud of its quality.

As we sipped several vintages of whites, reds and sparkling wine, Lily, our tour guide, told us of the numerous international medals Milestii Mici has won in various competitions. The winery's reputation is so good, she said, England's Queen Elizabeth and the royal family consume its red wine.

Moldova, which is about the same size as Maryland, is the seventh-largest wine-producing nation in the world. Wine exports constitute about one-third of the country's GDP.

Winemaking is not only a cornerstone of the Moldovan economy, but an integral part of its culture. Many Moldovans make their own wine at home and in some rural villages, a person's reputation is tied to the quality of their wine.

But Milestii Mici and other Moldovan wineries are now facing a serious challenge. A geopolitical wine war has erupted in Eastern Europe and Moldova is in danger of becoming its biggest casualty.

Until recently, 80 percent of Moldovan wine exports were sold to Russia. However, in late March, Russia announced that it would no longer buy wine from Moldova and Georgia, both former Soviet republics.

The official reason given by the Russian government was that wine from the two countries is unsafe to drink. A government official cited laboratory tests that reportedly found traces of DDT and heavy metals in the wine.

That's the official reason. But to many Moldovans, it all smells like sour grapes.

Since becoming independent from the Soviet Union 15 years ago, both Moldova and Georgia have increasingly been turning toward the West. Many view the wine ban as a Russian attempt to strong-arm the two countries back into a more submissive role.

Indeed, Russia has refused to publicly release its laboratory results and independent tests of Moldovan and Georgian wine have found no problems.

Further fueling Moldova's cynicism about the embargo is that the Kremlin hasn't banned wines from Transnistria, a mostly Russian-speaking separatist region in Moldova. Russian troops have kept the region's rogue government in power since a civil war 14 years ago.

At Milestii Mici, the ban is already taking a toll. Sales have slowed and workers have been given unpaid vacations. Other wineries have been forced to shut down completely.

Meanwhile, the country is desperately looking for new markets. Moldova's president recently visited Beijing in hopes of increasing wine exports to China.

The United States is another potentially lucrative market. Moldovan wine is already sold in 25 states. The hope is that American consumers will find Moldovan wine to be a good-tasting alternative to pricier French and Italian products.

Lily, our Milestii Mici guide, is optimistic Moldova's wine industry will withstand the Russian embargo.

"We will sell it somewhere else," she said. "We must do it."

15 Cents for the Bus Ride of My Life

May 11, 2006, by Dan Fellner

Article courtesy of Dan Fellner, published here with his kind permission; originally published in The Arizona Republic.

CHISINAU, Moldova - I had just delivered a guest lecture at a university located on the outskirts of Chisinau and needed to get back to the city center where I live.

My faculty host pointed me in the direction of a large white mini-van pulling up at the curb with a No. 127 placard in the windshield.

It was time to take my first solo trip on Moldovan mass transit. As I was about to find out, it wasn't exactly going to be a joyride.

Known as maxi-taxis, or marshrutkas in Russian, these 12-15 seat mini-vans, along with larger trolley buses, are the most common way Moldovans get around. With an average monthly salary of less than $100, few people can afford their own car.

Taxis, while cheap by American standards, are also too pricey for many Moldovans.

Maxi-taxis drive along designated routes throughout the city. They'll stop anywhere along the route to pick passengers up and drop them off. You signal for one just like you'd hail a taxi.

The trip started out pleasantly enough. As I climbed aboard, I handed the driver the fare of two Moldovan lei - a whopping 15 cents. There were only a handful of other passengers and I claimed a seat toward the front.

Some sort of Russian disco music was blaring from the radio and every time the van hit one of the many potholes on the road, it felt like the tires would fall off.

A few blocks later a woman standing on the side of the road raised her hand and the driver screeched the van to a halt. She opened the door and jumped in.

A minute later several more people got in, including an elderly woman. Feeling chivalrous, I relinquished my seat.

I was now standing in the aisle, holding onto a handrail above. The van stopped again. This time, five more people got in. The driver said something in Romanian, which I couldn't understand, but judging from the actions of the other passengers, he must have instructed us to squeeze toward the back.

It was suddenly getting very crowded. At least, I thought, we'd start making better time, as there was no way the driver would be stopping to pick up any more passengers.

I thought wrong. There were more stops and more passengers. My personal space was no longer mine and I felt like I could barely breathe.

Mass transit in Moldova is a claustrophobic's worst nightmare.

Each time the driver would slam on the brakes, our small sea of humanity would move forward in unison and then back again. I was getting seasick.

I hadn't had so much physical contact with so many strangers since I played eighth-grade football. It reminded me why I decided not to go out for ninth-grade football.

I looked around. None of the other passengers seemed to share my sense of discomfort. Some even talked nonchalantly on their cell phones. This is how Moldovans get to work or school every day and they're used to it.

I started to panic. There were so many people, I couldn't see out the window. Had we passed the place where I needed to get off?

Finally, after what seemed like an eternity but was probably more like 15 minutes, I heard someone say opriti

(stop), and the driver braked. A few people exited and I was able to get my bearings.

We weren't far from home. A block later, another passenger shouted opriti

and I followed him out the door. The driver hit the gas pedal even before I closed the door.

I had survived my first maxi-taxi ride. In the process, I had gained a heightened respect for Moldovans. They are a hard-working people who go about their daily lives - sometimes in rather unpleasant conditions - with good humor and without complaining.

As for me, the next time I need a ride, I think I'll call a cab.

Transnistria - I'm back in the U.S.S.R!

April 6, 2006, by Dan Fellner

Article courtesy of Dan Fellner, published here with his kind permission; originally published in The Arizona Republic.

It's real easy to get away from it all in a bizarre nation that doesn't exist

TIRASPOL, Transnistria - Greetings from the self-declared Republic of Transnistria, one of the most bizarre places on Earth.

Transnistria has its own government, army, flag and currency and controls its own borders.

In short, it thinks it's a country. The trouble is, no one else does.

This renegade region, the size of Rhode Island and home to about 600,000 people, is 50 miles east of where I am living in Moldova's capital of Chisinau.

Technically, Transnistria is within the internationally recognized borders of Moldova. But when Moldova became an independent country 15 years ago, this mostly Russian-speaking enclave decided to go its own way. A civil war erupted, in which 1,500 people died.

Since then, Transnistria has run its own affairs under the authoritarian regime of President Igor Smirnov. About 1,800 Russian troops help keep him in power. No country in the world recognizes Smirnov's government and Transnistria has become known as a haven for weapons and contraband smuggling.

I recently spent a day in Transnistria as part of a small delegation of Americans invited to lecture at the state university in Tiraspol, the capital of this non-existent country.

Not many Americans visit Transnistria, and I wouldn't have felt comfortable making the trip on my own.

As we sat in our van at the border crossing waiting for Transnistrian officials to give us the go-ahead to enter, I pulled out my camera, hoping to get a picture of the red-and-green-striped Transnistrian flag. It's not a flag you'll typically see pictured in an atlas.

An official seated next to me from the U.S. Embassy in Moldova suggested that it wasn't such a good idea. Several months ago, another American visitor also wanted to take a picture. Transnistrian border guards are notoriously camera-shy. They fired shots in the air until she relinquished her camera. I put mine back into my pocket.

As we drove through the streets of Tiraspol, I could see why travel books describe it as a living museum of the old Soviet Union. There were political billboards with the hammer and sickle, huge statues of Lenin and Soviet armored tanks on display.

At the university, I gave a lecture to a group of 60 students about America's mass media. With the help of a Russian translator, I discussed the vital role a free press plays in our democracy.

I got a lot of blank looks. Under Smirnov's iron rule, there is no such thing as a free press and people who voice dissenting opinions sometimes end up in jail.

A camera crew for the state-run television station shot footage of my lecture for use on the evening news and interviewed students about their impressions.

Apparently, it's news in Transnistria when a group of Americans comes for a visit.

After my lecture, our delegation dined with the university's rector. Over borscht and cognac, he told us the rest of the world had turned its back on Transnistria.

Our group listened politely. But I had other things on my mind. I wanted to go to a post office to buy highly sought-after Transnistrian postage stamps for my father, an avid stamp collector.

Others in our group wanted to buy Transnistrian-made cognac, considered quite good and an amazing bargain.

A couple of hours later, stamps and cognac in tow, our group crossed the border back into Moldova.

There have been on-again, off-again talks about resolving the Transnistrian conflict and possibly reuniting it with the rest of Moldova. Even the United States government has gotten involved.

But tensions in the region have escalated in recent weeks due to new customs rules imposed by neighboring Ukraine designed to halt the heavy flow of smuggled goods coming out of Transnistria. Smirnov has asked Russia to send more troops.

In the meantime, Transnistria remains a curious relic of Soviet times and an interesting place to visit for adventurous travelers who like to go about as far off the beaten path as you can get.

Culture buds in Moldova spring

March 16, 2006, by Dan Fellner

Article courtesy of Dan Fellner, published here with his kind permission; originally published in The Arizona Republic.

Festival marks the rebirth of life after hard winter

CHISINAU, Moldova - Spring officially arrived on March 1 with the beginning of a 10-day festival called Martisor.

It's a tradition dating hundreds of years in which Moldovans celebrate the rebirth of life after a hard winter.

There were several inches of snow on the ground and it sure didn't feel like spring. But my students at Moldova State University helped get me into the spirit of the coming season. As I entered the classroom, they lined up to pin special Martisor ornaments onto my sweater.

These beautiful pins, made of red and white thread and shaped into flowers, are a Moldovan symbol of friendship and respect.

That night, I went to a performance commemorating the beginning of Martisor at the National Palace Theater. Along with Vladimir Voronin, the president of the country, and hundreds of other Moldovans, I witnessed a wonderful display of singing and dancing by performers wearing colorful traditional costumes.

The best seat in the house cost less than $8 and it was as entertaining a show as anything I've ever seen at Gammage.

Perhaps the most enjoyable aspect of living abroad is getting the chance to become engrossed in another culture and thoroughly learn about a part of the world so different from Arizona in so many ways.

Moldova is a poor country, yet Moldovans are some of the most generous and welcoming people I have encountered. Each day when I arrive at the university, I am met at the school of journalism office with a warm greeting of buna ziua (good day) and a cup of hot tea.

Despite being warned that the students would sit in class stone-faced and silent - a common stereotype of Eastern Europeans - I am finding them to be energetic, responsive and participative. Class discussions are as lively as back home.

My courses are conducted in English, which is a bit of a struggle for some of the students, but everyone is able to speak the language well enough to get by.

I'm not exactly sure why, but journalism students in most Eastern European countries tend to be overwhelmingly female, and that's also the case in Moldova.

In fact, all of my students in both classes I'm teaching are female.

Many of them are working as journalists at major media outlets in the country. Moldova, which has been an independent country for 15 years, is still building a free press and there are opportunities for young people to enter the field and get meaningful on-the-job experience while still completing their studies.

Only one of my students has been to the United States and most of them have had very little direct contact with Americans.

I try to allot a few minutes at the end of each class for general questions about America.

They are teaching me Romanian words and about their country's history and customs, including Martisor. I think I am learning as much from them as they are from me.

According to Martisor tradition, you're supposed to wear the pins until the trees bloom, at which time you hang them on a branch for good luck.

But I'm going to break with tradition and keep my Martisor pins. They are a special memento of my students and spring in Moldova.

Moldova

February 15-22 2006, by Rob Crossan

Time Out London Issue 1841: February 15-22 2006. I obtained the permission to publish only the first two paragraphs from the article. Please see the full feature here

We visit Chisinau, Moldova - one of Europe's most obscure and cheapest capital cities.

There is an enormous army tank on the dancefloor. Peering out of the gun porthole is a manic-looking DJ whose decks are hidden inside. To his left is a pile of sandbags and a hammer-and-sickle USSR flag. Hanging from the ceiling is a giant portrait of Lenin. Taking all this in is hard for a first-time visitor. Uniformly sultry and beautiful Moldovan women pack the dancefloor and around the room more svelte women and their companions down the local speciality of three different schnapps in one glass.

Then the increasing sense of the surreal gives way to outright lunacy as the dancefloor of the Chisinau 'Military Pub', packed on the early hours of a Tuesday morning in the middle of winter, grinds to a halt. The barman is vigourously ringing his bell. The lights dim as the bell rings louder and grimaces give way to cheers as the imbibers bounce off the bar counter and back on the dancefloor to a collective cheer. My local boozer in Stockwell suddenly seems like a drinking emporium from a different and vastly more boring planet.

Asking for salsa in Moldova draws a blank look

February 21, 2006, by Dan Fellner

Article courtesy of Dan Fellner, published here with his kind permission; originally published in The Arizona Republic.

CHISINAU, Moldova - It was my first Saturday night in Moldova and already I was starting to feel a bit homesick. I needed something to remind me of home.

The U.S. Embassy had given me a welcome packet when I arrived, which included a list of recommended restaurants. A place on the list called "Cactus Saloon" caught my eye. "Mexican food, Moldovan style," the description read.

It was in the low 20s outside and the icy sidewalks and dimly lit streets made the 20-minute walk to 41 Armeneasca St. a bit dicey. But I wanted a taste of home - preferably in the form of chips and salsa followed by a bean burrito or chicken fajitas.

I arrived at the Cactus Saloon and immediately was impressed by two things. The place was packed, always a good sign. I grabbed the last empty table. And the decor truly looked like a Mexican restaurant, with pictures of the Old West and Mexico and even one of those swinging saloon-doors. A mariachi band wouldn't have seemed out of place.

Eastern European cuisine is notoriously bland but I had high hopes. Did the Serrano family have a distant cousin living in Chisinau?

My waiter, Nicolai, brought me a menu. Every dish was listed in three languages - Romanian (the dominant language in Moldova), Russian and English. But it might as well have been in Greek, because nothing looked remotely familiar to me, with the exception of Corona beer (priced three times higher than the local beer).

No tacos, tostados or tortillas. They had all sorts of chicken, meat and fish dishes, even soy meat, but all prepared in ways that seemed to be anything but Mexican.

I called Nicolai over to the table. "Excuse me," I said. "Do you have anything spicy?" He mentioned some sort of "balsamic" sauce they had prepared and a dish involving chicken and almonds. I knew that wouldn't satisfy my craving.

"Don't you even have any salsa?" I asked.

Nicolai gave me a blank look. It was clear he didn't understand. "Salsa," I repeated more loudly, thinking he hadn't heard me over the music blaring from the restaurant's sound system.

"Oh yes, salsa," he said. "I will check in the back."

While I waited for him to return, I remembered the time I had asked for salsa at a "Mexican" restaurant in Latvia, another country in Eastern Europe. They ended up bringing me a bowl of ketchup with pepper poured on top of it. Maybe I should have just kept my mouth shut.

"I am sorry," Nicolai said after returning from the back. "No salsa. We only play rock 'n roll and maybe a little jazz."

There would be no salsa for me this night.

As it turned out, though, the meal was quite good. I had chicken in some sort of mystery sauce with potatoes and a roll on the side. It just wasn't what I had expected.

That's the key to enjoying a Moldovan dining experience. Leave your pre-conceived expectations at the door, because you never quite know what you're going to get. You do know it's going to be different than back home, and that's part of the fun.

My very first day in Moldova, still jetlagged from the 24-hour journey, I ordered something that I thought would be harmless comfort food - a vegetarian pizza. Then they brought it out. It was drenched in mayonnaise.

Indeed, Moldovans, like most other Eastern Europeans, love cream sauces, cheese, mayonnaise and other dairy products. Order a bowl of soup, and chances are it will come with a big glob of cream floating at the top. Cardiologists here never have to worry about running out of patients.

But I've had some meals that were wonderful. And you can't beat the prices. Most meals out cost between $5 and $10, and that includes a glass of Moldovan wine, which is quite good.

When I truly long for the taste of home, there's always McDonald's. Chisinau has three of them. A Big Mac is a Big Mac, wherever you go.

As for my quest for salsa, I finally found it. Believe it or not, Chisinau actually has two Mexican restaurants. The second one I visited - called "El Paso" - was much more authentic. They even brought chips and salsa to my table as I was seated.

I've also learned to be more careful when I order. From now on, I specify "no cream" when ordering soup. At a pizza place, I ask for pepperoni and black olives. And please, hold the mayo.

From sunshine to Moldova

January 31, 2006, by Dan Fellner

Article courtesy of Dan Fellner, published here with his kind permission; originally published in The Arizona Republic.

CHISINAU, Moldova - It's 7,000 miles and nine time zones between Gilbert and Chisinau, Moldova. It actually feels like it's much farther than that.

Through the blowing snow outside the living room window of my second-floor apartment on Nicolae Iorga Street, I can see a statue of Vladimir Lenin in the courtyard of Moldova's Communist Party headquarters.

It isn't a monument to a bygone era. Moldova, which endured a half-century of totalitarian rule as part of the Soviet Union until it emerged as the independent Republic of Moldova in 1991, has returned to its communist past. Its people elected a slate of communist leaders in 2001 and re-elected them last year.

But Moldova's version of communism would make the real Lenin spin in his grave. Communism here is much less ideological than the past and much more user-friendly. There are no forced labor camps, no KGB, and no bread lines. There are, however, free elections, a free-market economy, and the country is moving toward European integration.

Moldova also enjoys solid relations with the United States. Heather Hodges, the U.S. ambassador to Moldova, calls the relationship "positive and productive." Moldova is even part of the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq, having sent 65 troops there since 2003.

Landlocked between Ukraine and Romania, Moldova has a population of about 4 million people. Like many countries in this part of the world, it's been batted back-and-forth between invading powers over the centuries and has struggled to maintain its cultural identity.

Moldovan is the country's official language, but is as similar to Romanian as American English is to British English. Most Moldovans also speak Russian and it's not uncommon for young people to speak at least a little English, which is widely taught in the schools.

Moldova's economy, which was highly dependent on the rest of the Soviet Union for energy and raw materials, took a huge hit when the USSR disintegrated 15 years ago and has yet to fully recover. Today, it's the poorest country in Europe, with an average salary of less than $100 a month. Many people need to hold down two or more jobs just to make ends meet.

Because wages are so low, an estimated one million Moldovans - mostly young people -- have left the country in recent years to find work in other European countries. A Moldovan engineer or college professor can increase his or her salary tenfold by working as a construction worker in Portugal or housekeeper in Italy.

This exodus is part of the reason the communists have returned to power. Ghenadie Slobodeniuc, my landlord's a 28-year-old son who is a lecturer in international relations at Moldova State University, tells me that the communists garner much of their support from older Moldovans who've remained in the country, turn out at the polls, and fondly recall the days when bread was cheap - even though you had to stand in line to get it -- and everyone was guaranteed a job.

"They are living in the past," says Slobodeniuc, of the older voting bloc. "They are afraid of change."

He adds that more centrist parties, which held power in the years after independence, failed to keep their promises and were rife with corruption. So the communists seemed like a palatable alternative to a majority of the Moldovan electorate.

But as Ambassador Hodges notes, corruption remains "endemic and affects all aspects of Moldovan life." And Slobodeniuc and other Moldovans with whom I've spoken are skeptical that government -- in any shape or form -- can significantly improve things.

I am living in Chisinau (pronounced kish-i-now), the capital and largest city, with a population of about 700,000. For such a poor country, I'm amazed at how many Mercedes and BMWs I've seen and some of the high-end boutiques here wouldn't look out-of-place in Scottsdale. Like a lot of other developing countries, there's a huge gap between the rich and poor.

During my second week here, a record cold spell hit Eastern Europe and temperatures in Moldova plunged to 10 degrees below zero, the coldest weather in more than a decade. Fortunately, the apartment the U.S. Embassy arranged for me has dependable heating and hot water. It's something we take for granted back home, but here in Moldova, it's considered a luxury that a good segment of the population can't afford, particularly those in rural areas.

I'm just a five-minute walk from the university at which I'm teaching and plenty of stores and nice restaurants are close by. Street crime is lower than in many American cities.

The biggest danger for me has been navigating the sidewalks. Most of them haven't been cleared of snow and are treacherously slippery. And I've been warned not to walk down side streets after dark because of the prevalence of open manholes. It seems the covers sometimes get stolen and sold for scrap metal.

While Moldova isn't known as a tourist destination, there are some interesting things to see here - ancient monasteries and some of the best wineries in Eastern Europe. I look forward to exploring the country.

But for this Arizonan, it's a bit too cold now to do much sightseeing and venture far from my apartment. For now, at least, I'll have to be content with my reliable radiator and view of Lenin.

Moldova: A Small Wonder (...and Information On Upcoming Tour To Romania)

April 2005, by Kevin Stillmock

Article courtesy of Kevin Stillmock, published here with his kind permission; originally published at EscapeArtist.com.

Moldova or Moldavia as it is officially known in English is not the first stop on most people's tourist itinerary. This small landlocked country of just over 4 million people is virtually unknown to the outside world.

When I came to for a (never-to-be) business meeting in Chisinau (pronounced kishy-now) I wasn't sure quite what to expect. The travel agent who sold me the ticket, strangely advised me several times to abandon my plans and go somewhere else. Most of my friends and acquaintances were confused just as to where it was that I was going to in the first place. On several occasions I was asked if I was worried about getting malaria while in Africa, I was also chastised for making up the name of a fake country to protect my anonymity and questioned if the idea to come to Moldova came to me after hearing about it in a Marx Brothers movie.

By now, you might be wondering, just where in the world is Moldova? It is not, as it's former makeshift tourism board claims a place where you can "spend a varnishing day in the center of Europe." (whatever the heck that means) Rather, it is about as far east as you can get in Europe. This former Soviet member country is named after the providence of Moldavia located in Romania of which most of it used to be a part.

I will never forget the first time my plane landed at the Chisinau International Airport. The small commuter plane I had taken from Vienna touched ground and my first view of Moldova on an overcast day was of old Russian-style tanks, soldiers, and guard dogs. I thought perhaps I had accidentally boarded a Con-Air flight.

I confess that I was like a fish-out-of water the entire time during my intended two week stay. Since my original hosts had never showed up, I was totally on my own. I was baffled by the multiplicity of languages spoken. Although barely the size of my home state of Maryland (also abbreviated MD and at about the same longitude - about where the similarities end) there were no less then 4 languages commonly spoken: Moldovan (a dialect of Romanian), Russian, Ukrainian and Gagauzian. I was stopped on the street a number of times and asked the time in the Moldovan language and responded Ya ne gavaru pa rusky. "I do not speak Russian." Got a lot of strange looks. I ordered "alphabet soup" but later discovered that it was a mistranslation for "tongue soup." Trust me, bye the way, alphabet soup is better. Much better.

This small country, that I had never heard of before, is in fact three different countries in one. The southern half is the Republic of Gagauzia, where Christianized Turks had settled years ago. They are recognized by the Moldovan government and seem to be at peace with them. Then there is the self-proclaimed Republic of Transdniestria, perhaps the most surreal place on earth. On my visit there (in which my friend and I were rescued in a special mission from the US Embassy - this is another story) we saw what could only be described as a living museum to the Soviet Union. Statues of Lenin were being put up before our eyes, bread lines were long, and we were ticketed for looking the wrong way when crossing the street.

All of that being said, I thought I had saw all I needed of this "Moldovan trinity" for one lifetime. I had my bags packed and was ready for home, sweet home. However, I was soon to discover that I would have been making a colossal mistake.

There was something that I had overlooked. There was something important that I had missed during my two week tour of this fascinatingly "other" country.

Moldova has no coastline. Moldova has no mountains. Moldova does not possess a year-round pleasant climate. Moldova requires a $60 minimum visa for entry and can't seem to set up a stable government . Yet, with all of this taken into consideration, I just can't stop returning to this place! I consider it one of the best kept secrets on earth, in fact. And, I am not alone.

What is it that I had almost overlooked that continues to draw me to Moldova?

It could be the wine that keeps me coming back. After all, much of Moldova is a steppe to the Carpathian Mountain range, possessing the perfect soil for wine production. Moldova produces a variety of excellent wines (which sold in London pubs in Soviet days for about $125 a bottle) that sell for less than the price of a bottle of Coca Cola in local grocery stores. It is also home to the world's largest underground wine cellars at "Cricova." A whole underground world, it's registers in at a whopping 60 square kilometers in size, with streets named after famous wines and medieval style tasting rooms. It is a must for any wine connoisseur. So, is the annual Wine Festival every autumn, organized in conjunction with the Moldovan State, which offers foreign visitors free visas during the time of the festival.

A well-guarded legend, published here for the first time, is that Hawaiian singer Don Ho, who came to Moldova to perform a concert, became so tipsy after a sipping tour of the Cricova facilities earlier in the day that he barely made it through 3 songs before excusing himself from the stage. From what I hear, the easy-going Moldovan concert-goers didn't seem to really mind.

It could be that very easy-going nature of many Moldovans that keeps me coming back. Their nature is supported by large and frequent concerts that close down much of the main street and that are of course, totally free. You have to appreciate a people and a city that despite all the hardships it has had to face stops traffic regularly to dance the hora and kick back a beer. That's my kind of place.

It could be the unspoiled village life and nature found just outside the city. If you've never been to a real Eastern European village, your missing out on an unforgettable experience. There are few places on earth where people who don't know you, will slaughter five animals in honor of your arrival and invite the whole neighborhood to drink homemade wine and vodka with you. Moldovan villages are such special places!

In this neck of the woods, bathrooms are still outhouses, outside lighting has yet to be invented, and modern farming technology exists only for the lazy.

But, just when you feel like you could be no further from civilization, you might, like I, hear the familiar tunes of Britney Spears coming from one of the bedrooms of a local child!

I'm not really one for the quiet life though, so maybe this also isn't the main reason why I love Moldova. I like the night life and fun times. Chisinau is so hopping that the New York Times devoted a full story to Chisinau's club scene! A half-million dollar, futuristic super-clubs challenge the finest clubs of Western Europe and America. A good example of what one looks like can be seen by watching the Eastern-European club scene in the popular movie "Euro Trip."

Moldova is a stopping point for refugees who have opened up their own clubs and restaurants, adding an eclectic, cosmopolitan air to the city; this has helped create an excitingly diverse nightlife.

All partying and having fun can, believe it or not, get pretty tiring. So this too is not the reason I am so sold on Moldova.

It could be the gentle air of familiarity found Chisinau that makes me love this place so much. Chisinau offers all the amenities of a big town - restaurants, opera, cinema, clubs, and more, all without most of the hassles that big city life entails. Plus, most everything is an easy walk. And everyone is out walking. In fact, it's impossible for me to walk in the city for five minutes and not run into two people that I know, even if I haven't been in town for a year!

Chisinau is a surprisingly clean city and has recently been renovated in the downtown area. One could even say its become posh. It is almost unrecognizable from how it was when I first visited in 2000. While always preserving it's many layers of rich history, Chisinau is always evolving, always growing, holding new surprises in store for me each time that I return.

I suspect that this is also why almost every ex-pat I have met in Chisinau seems to love it. One ex-pat explained to me that he felt like a member of an elite club. Part of the 'chosen few' lucky enough to know about the existence of this place.

But none of these are the reasons that I just can't stop coming back to Moldova, all though they certainly add to my enjoyment and appreciation of Europe's most hidden country.

The real reason is actually profoundly simple - the wonderfully genuine and sincere nature of the Moldovan people. Anywhere on earth you will find good people and bad people. That is a given. Moldova, however, seems to have a disproportionate number of good people. I mean really good. Not goody-two-shoe-good but genuine, salt of the earth good. Reliable, trustworthy, friends for life. It's been said if you can count your true friends on the five fingers of your hands, you are rich. If that's true, then Moldova stands to make you a very rich person.

Now, you may be thinking, that this is simply my personal experience. It could have happened to me anywhere. It is just happenstance that I met so many wonderful people in Moldova. Maybe you're right. I can only say that I have traveled to many countries and met many wonderful people and spoke with many ex-pats in those countries. Nowhere have I met as many ex-pats who have told me about how wonderful and open the locals are, and what good friends they've made in Moldova.

The people there are less affected by the declining value placed on friendship in the West. When I asked several hundred young Moldovans what are the five most important things in your life the most common replies were "My faith, my family, my friends, love, making a difference in Moldova and the world." A similar poll in America yielded much more materialistic results from it's participants. This difference in perspectives affects not only the individual adherents but the society-at-large in profound ways.

Sure, old traditional mentalities are not always healthy, and Moldova's growth has been hampered by less positive mentalities which also unfortunately continue to persist. The less wonderful side of Moldova though only helps serve as a magnifier of the wonderful side filled with great people and traditions.

So while the common accusation of Moldova's being "trapped in the past" may not seem so good and certainly is far from being a totally true declaration, I can only say judging from my experience, I like spending some time "trapped in the past."

Moldova's greatest asset in the end is not its wine, its clubs, or the layout of its capitol city. It greatest asset is its people.

They are why you will love Moldova.

Moldova is a true original with a character all its own. It possesses a compelling otherness that will always stay with you and a people who will capture your heart. That is why you too, may end up coming to Moldova again and again.

Moldova makes a great trip from Romania by car or plane and from other European countries via direct flight. It will definitely add a unique aspect to your vacation that most other travellers still don't know about. You may even decide to stay a little while longer like I did. Most ex-pats I meet in Moldova, in fact, came there for a few weeks, or a few months, a few years ago.

My final advice, if you come to Moldova is to try to buy an airline ticket that has an open-ended return. Odds are it will come in handy.

Moldova Footnotes

For a good meal

Green Hills Nistru - With three central locations, Green Hills Nistru is a Chisinau legend. Go here and a good meal is virtually guaranteed. The menu is diverse, international, with prices that make this dining experience a must. Try the chicken goulash, my personal favorite, that comes with a side of rice for less then $4. Centrally located on Stephan Cel Mare Boulevard next to the Organ Hall, Mihai Eminescu street (on the same corner), and on 31 August 1989 street next to the excellent Symposium French restaurant, which is run by the owners of Green Hills Nistru.

New York - Missing home? Try the the Turkish-built entertainment and dining experience that is a true hit. The food combines the best of American, Turkish, and Moldovan fare in perfect presentation. Sit by the window at night time and you will see the New York skyline. Work off the calories with a game of bowling in super-modern alleys, in a country where bowling is considered "hip" or play a game of billiards or one of the many electronic games housed in the New York complex. You'll forget that you're more then 7,000 miles away from the Big Apple in no time! Located next to the Hotel Dedeman across from ULIM University in the City Center.

Other Must-Sees

So-Ho night club, City Club night club, the Circus,the Organ Hall, the Opera House, Kathmandu African Restaurant, De-Ja-Vu bar, the Cricova Underground wine cellars tour. Use the contact information below or ask your hotel concierge for directions and more information.

Useful Web Sites

Cricova Wine: http://www.cricova.md/eng/, http://www.cricova.md/eng/cellars/

Pictures of Moldova: http://www.photo.md

Tourism: http://www.turism.md/eng, http://www.welcome-moldova.com/

Moldova's Curious Growth

January 21, 2005, by Vitalie Dogaru

Article courtesy of Transitions Online, published here with kind permission from Lars Nicolaisen.

Europe's least-developed country is boasting some impressive growth figures. Pity the growth isn't helping the economy very much.

CHISINAU, Moldova - When the United Nations rates your country as the least-developed country in Europe, and 109th out of 175 in the world, any economic growth is welcome. So it was perhaps understandable that Moldova's prime minister, Vasile Tarlev, exclaimed happily, Look what industrial growth we have!

when faced with sceptical economists from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in October. He certainly has some good figures to point to. After three years of growth, Moldova's economy is still picking up speed, achieving a record 6.1 percent increase in economic activity in the first half in 2004.

It must have been all the sweeter to say so to these two institutions because, in 2003, the IMF, which coordinates closely with the World Bank, suspended most of a $147 million financing program on the grounds that the Moldovan government had failed to take steps agreed upon with the IMF.

At that time, local experts, influenced by IMF and World Bank representatives, were predicting that the isolated Moldovan state would go bankrupt, but we have achieved a lot,

the prime minister said after the IMF and World Bank meeting, using a refrain heard repeatedly in recent years.

And for Tarlev and his Communist government, statistics indicating that Moldova is growing faster than ever (feeding government forecasts that the economy will expand by 6 to 8 percent this year) are particularly welcome now: in February, the country will vote for a new parliament, which will in turn vote for a new president.

ONE STEP FORWARD

But for the World Bank, still full of angst about Moldova's failure to liberalize its economy, the growth is not a sign of health but a symptom of an illness. During a visit to Moldova in October, the bank's vice president, Shigeo Katsu, even said that Moldova was taking one step forward, two steps back.

The IMF's chief negotiator with Moldova, Marta Castello-Branco, echoed Katsu's concern, worrying that the growth is not a sign of a healthier economy.

Some of the headline figures certainly look good: industrial production in the first six months was 16.7 percent higher year on year, and exports climbed by 36 percent. But, according to the IMF, much of the growth is in production of consumer goods, and most of the imports are consumer goods. Little money is being invested, and there is little sign that Moldova is producing higher-value-added goods.

The IMF and the World Bank attribute this rise in consumption to money sent back by Moldova's migrant workers.

Nobody quite knows how many Moldovans work abroad, but the number is huge. A report earlier this year from the Soros Foundation and a Moldovan partner, the Alliance for Microfinancing, found that one in three Moldovan families has a family member working abroad. Moldova's population is officially put at 3.6 million; between 400,000 and 1 million are gastarbeiters, or guest workers, elsewhere.

In 2003 alone, 300,000 of people of active age left Moldova in search of work, according to the Soros report.

These are not Moldova's unemployed and poorly skilled. In fact, two-thirds of these migrants also hold down a job in Moldova, one-third of them work in the public sector (as teachers, doctors, and civil servants), and a full half of them have a higher education.

The pattern of migration seems fairly clear. The poorest head east or south, overwhelmingly to Russia (the destination for 60 percent of Moldovan workers) but also in significant numbers to Turkey, Greece, and Cyprus. Although salaries there are lower than in Western Europe, the travel costs are also lower and the risk of being caught and sent home is minimal. When they have earned enough money there, they follow their wealthier countrymen and try to reach Western markets. Mostly, they head for Italy, Portugal, and Spain (30 percent of Moldovan migrants now work in these three countries) since immigration controls are tougher in other West European countries.

ONE STEP BACK

These workers are, of course, leaving to better their own lives, and one survey, with data ending in September 2003, indicates that the average Moldovan saw his monthly income rise from 279 lei ($22) to 1,700 lei (roughly $140) after heading abroad. But they are not keeping the money to themselves. The same survey indicated that remittances account for 85 percent of the family budget of migrants' immediate families.

Almost everyone interviewed for the Soros Foundation report (94.7 percent) said they sent money home. And the sums are significant: the average migrant family receives $2,985 a year from those of its members working abroad, according to the same report.

This may be a lifeline for many, but it causes complications for the economy. The immediate problem is that the inflow of cash is artificially strengthening the lei, making life harder for exporters. (It also reduces the value of the euros and dollars that migrant workers send home.)

Beyond that, some believe that a cycle of migration is being created. The money sent back is often used by other members of the family to migrate. It also creates a structural inequality between those who work abroad and those who remain in Moldova. Firstly, gastarbeiters do not pay income tax (in fact, since most money is sent back through informal channels, they also avoid other taxes). Secondly, the inflow of cash increases the price of products, and families who do not have members working abroad find that goods such as refrigerators and washing machines, not to mention cars or apartments, are increasingly inaccessible. This in turn encourages more migration.

And the money appears to be doing little lasting good for the economy, because the money from remittances is not being invested, but spent. According to the Soros Foundation research, families said that, in addition to funding migration by other members of the family, the money was being used for repaying debts, for housekeeping, for loans to relatives and friends (mainly to fund their migration), and for buying consumer goods. Only a small proportion of the remittances - 6.5 percent - is used to set up shop (or set up any kind of business) in Moldova.

Of course, after years of austerity, who can deny Moldovans the right and desire to buy refrigerators, washing machines, and boilers that work, plus the occasional exotic fruit and some attractively designed furniture? There is nothing wrong with buying items that are necessary, comfortable, and (sometimes) tasteful - and who could resist the temptation offered by the mushrooming number of Western-style supermarkets?

But other explanations can also be found. There is, of course, the legacy of communism, which left Moldovans with no experience and tradition of running their own businesses. On top of that, there is the psychological legacy of the tough years of barely comprehensible transition to capitalism in the 1990s, a legacy that has superimposed images of racketeering, the black economy, and the mafia on notions of business.

More prosaically, the lack of investment may actually simply reflect the nature of migration. After all, if those of working age have left home to work abroad, who is left to tend the shop and develop a business? Just the old and the young.

But whatever the causes, one local analyst warns that, unless this changes, Moldova will be transformed into a "country cottage," a place to sleep and live off money sent back by next of kin working abroad.

(The analogy seems all the truer because the only form of investment that Moldovans seem to trust at the moment is in bricks and mortar, in apartments and houses.)

A SECOND STEP BACK

Still, the reluctance of Moldovan gastarbeiters to invest their money in Moldova may be a secondary problem that, over time and in the right environment, might resolve itself. Eventually, even the small number of Moldovans gaining experience in setting up and managing a private small business in their own country may encourage greater entrepreneurship. The migrants' strong educational background should also help.

The primary problem is that the government is failing to create a friendly and encouraging business climate. Setting up a business is a tangled and time-consuming affair - and the new businessperson faces hefty taxes from the moment he begins operating. In such an environment, it can seem a better investment to head across the border to work.

Just how unfriendly the climate is becomes clear when one looks, for example, at the dismal inflow of foreign investment in Moldova. In 2003, only $69 million was invested in the country, just 11 percent or so of the estimated $600 million remitted by migrant workers. With so little investment, either from Moldovans or foreign companies, few jobs are being created.

That points to the failure of the government to liberalize the economy, a criticism made by the World Bank and the IMF. The government has in the past year made some attempts to make the legislative framework more attractive for investors, but they are relatively peripheral. It has also launched a public relations campaign to promote Moldova's image abroad (in fact, much of the effort is simply to make people realize Moldova exists). But nothing it has done can undo the damage caused by the actions the Communist government made in its first days in power. And nothing has yet persuaded the IMF to agree to a new set of loans.

In 2001, it annulled several important earlier privatization deals--involving, for example, the drug company Europharm, Air Moldova, and the Hotel Dacia--and it put pressure on foreign investors such as the French cement-maker Lafarge and investors in the electricity distributor Union Fenosa.

The effect has been bad for some of the companies involved. Within two years of being renationalized, Europharm, a once-flourishing American-Romanian joint venture, was bankrupt. It has also been bad for foreign direct investment, which fell from $126 million in 2001 to $69 million in 2003, and it has reinforced investors' fears of a Communist government.

Jobs that could be created with investment by migrant workers and by foreign investors are not, then, being created. And, without these reforms, the World Bank and the IMF are unlikely change their arm's-length approach.

The government remains defiant. The Moldovan government is determined not to repeat the vicious practice of asking for external credits, including commercial, no matter how difficult the internal situation will be, to cover gaps in the budget,

Tarlev has said.

The government can afford to take this approach partly thanks to the volume of money being sent home, a lifeline that conveniently reduces social tensions. The strength of Moldovans' family ties and the way they operate as an economic unit is carrying them and perhaps even the government, which continues to lead in opinion polls, through tough times. Shame, though, that Moldovans can't find work at home and remain with their families.

Wheat Swamp to Moldova a Long Way

December 30, 2004, by Karen McConkey, Staff writer

Article courtesy of The Kinston Free Press (Kinston, North Carolina), published here with kind permission from Patrick Holmes.

It's a long way from Wheat Swamp to the eastern European country of Moldova. But you can get there from here, says Lenoir County Emergency Services Director Roger Dail. "It just takes a very, very long time."

"When I first heard I was going, I just started laughing," Dail said. "I thought, you've got to be kidding. Why would I be going to Russia?"

Dail was selected by North Carolina's Emergency Response team to fly to Moldova and teach officials there how to set up a management plan in the event of a disaster.

Dail's experiences in responding to the 2003 explosion of West Pharmaceutical Services prompted state officials to use Lenoir County's emergency response plan when Moldova asked for guidance.

"The state and Moldova have a kind of exchange plan," Dail said. "It's like exchange students. We learn, we teach, we share information. They had asked for some help setting up a disaster management plan. So I went over there to share with them the pros and the cons of how the county handled the West company disaster."

After a flight of more than 24 hours, Dail arrived in the country where he was met by American Embassy representatives. Two United States military reservists were assigned to help with the training sessions during the week Dail was there.

"They took me to a hotel, and I mean, it was a hotel," Dail said. "A five-star hotel. The thing about that, though, it only had five rooms. But they were very, very nice."

Moldova is about the size of Maryland. The capital, Chisinau, was where Dail held training sessions with Moldovian military and civilian representatives.

"They were very interested in learning everything they could," he said. "In Moldova, there aren't fire chiefs or police chiefs, like we have here. Everyone is called a 'minister' of something."

One day, after a session, a Moldovian attending the training session invited Dail and his two reservists back to his home.

"These people are very, very nice and they like Americans," Dail said.

The man invited Dail to his basement to look at his wine cellar.

"The irony of it is that the wine cellar used to be a bomb shelter," Dail said. "He told me that as late as 1979, the Russian people were being told they needed to protect themselves against American bombs. I said, 'Man, we quit doing that in the '60s; we had a good laugh about it."

Chisinau has maintained its old European ambience. The poor economy has restricted any real growth or modern advancement.

Moldovians revere higher learning, Dail said.

"They believe in education, in advanced education, but there is really nowhere for the young people to work if they receive an advanced degree," he said. "The young people love America. They really want to come to America and live. They learn the language and don't call it 'English.' They call it 'American.'"

Few, if any, cultural differences were apparent. The only significant one was customary breakfast fare. The first morning Dail went downstairs at his hotel for breakfast, he ordered toast and coffee.

"I got a tiny little cup with coffee, and bread that was as hard as the table, along with some cheese and butter," he said.

Dail decided to take his chances with boiled eggs that were featured on the menu.

"When they brought them to the table, I knew I was in trouble," he said. "They were sitting in those little egg cups, and when I cut the top open, they were still runny. I said, 'Roger, there's just no way you're eating that.' "

Dail left the country feeling accepted and welcomed. He also felt the impact of coming back to the United States in a way he hadn't felt it before.

"I couldn't help but think about how many things we have to be grateful for," he said. "There are so many things about this country that people in other countries envy, things we just take for granted like having a home, or a piece of land or a car. I came back feeling very grateful for all we have."